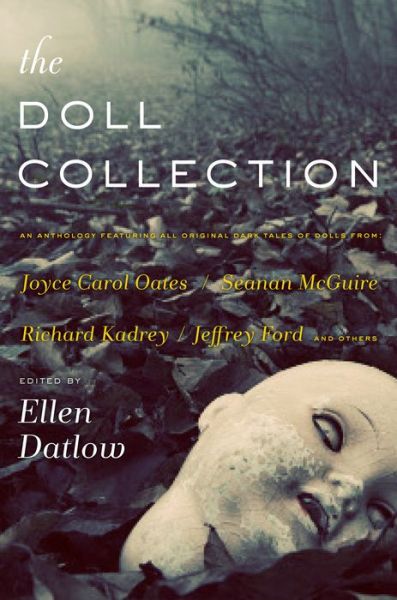

The Doll Collection—available March 10th from Tor Books—is an anthology designed to frighten and delight, featuring all-original dark tales of dolls from bestselling and award-winning authors compiled by one of the top editors in the field, a treasured toy box of all-original dark stories about dolls of all types, including everything from puppets and poppets to mannequins and baby dolls.

Master anthologist Ellen Datlow has assembled a list of beautiful and terrifying stories from bestselling and critically acclaimed authors. Featuring everything from life-sized clockwork dolls to all-too-human Betsy Wetsy-type baby dolls, these stories play into the true creepiness of the doll trope, but avoid the clichés that often show up in stories of this type. The collection is illustrated with photographs of dolls taken by Datlow and other devoted doll collectors from the science fiction and fantasy field. The result is a star-studded collection exploring one of the most primal fears of readers of dark fiction everywhere, and one that every eader will want to add to their own collection.

Dolls, perhaps more than any other object, demonstrate just how thin the line between love and fear, comfort and horror, can be. They are objects of love and sources of reassurance for children, coveted prizes for collectors, sources of terror and horror in numerous movies, television shows, books, and stories. Dolls fire our collective imagination, for better and—too often—for worse. From life-size dolls the same height as the little girls who carry them, to dolls whose long hair can “grow” longer, to Barbie and her fashionable sisters, dolls do double duty as child’s play and the focus of adult art and adult fear.

Some dolls were never meant for children at all. Voodoo dolls, for example, are created as objects of transference and loci of power; effigies of hated figures such as Guy Fawkes are created specifically in order to suffer violence; shrunken heads were used for religious purposes and as trophies; and Real Dolls, anatomically correct life-size models of women, are made for men who prefer their sexual “partners” lifeless and mute.

I myself collect dolls (including three-faced dolls—dolls that, given a turn of the head, will show a baby sleeping, crying, or smiling, as long as you don’t mind twisting your doll’s neck), doll heads, and other doll parts. That physical collection has led to this collection of dark fantasy and horror stories of dolls and their worlds.

Of course, I am hardly the first to see the connection between dolls and terror. Evil dolls are practically a subgenre of horror fiction and film: 1936’s The Devil-Doll with Lionel Barrymore as the mastermind behind a set of murderous dolls; 1975’s Trilogy of Terror, wherein Karen Black is menaced by a Zuni fetish doll (based on the short story “Prey” by Richard Matheson); the 1976 William Goldman novel Magic, an example of the ever-popular “evil ventriloquist’s dummy” subset of doll horror; the 1960 Twilight Zone episode “The After Hours,” in which mannequins long for lives of their own; and of course the Child’s Play franchise, featuring the homicidal Chucky, which first saw light in 1988. More recently, 2013 saw the release of The Conjuring, featuring Annabelle, a possessed doll, whose own spin-off was released in October 2014.

With this venerable tradition in mind, when I approached writers about contributing to this anthology, I made one condition: no evil doll stories. While these writers could and did mine the uncanniness of dolls for all it’s worth, I did not want to publish a collection of stories revolving around the cliché of the evil doll. Surely, I thought, there was horror and darkness to be found in the world of dolls beyond that well-trodden path. As you shall shortly see, I was right: the dolls and doll-like creatures within range from the once-ubiquitous kewpie dolls created by Rose O’Neill, which were often given away as prizes at carnivals and circuses; to a homemade monster created out of a repurposed Commander Kirk doll; to a Shirley Temple doll come upon hard times; to unique dolls and doll-like objects created from the imaginations of the contributors to punish or comfort humans, or placate the inhuman.

Sigmund Freud, in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” noted that dolls were particularly uncanny, falling into the category of objects that look as though they should be alive but aren’t. But he also suggested that uncanniness in general was the result of something familiar that should have been kept secret instead of being brought to light—the cognitive disjuncture produces that feeling of unease which we attribute to the uncanny. What do dolls bring to light? In these stories, what they so often highlight is the malevolence that lurks not in dolls—which are, after all, only poor copies of ourselves, only objects at our mercy—but in the human beings who interact with them. Not horrific in themselves, but imbued with horror by their owners or controllers, what the dolls in these stories often reveal is the evil within us, the evil that we try to keep hidden, but that dolls bring to light.

Theories of uncanniness have been elaborated upon since Freud’s time. The “uncanny valley” refers to a theory developed by robotics professor Masahiro Mori in 1970: It posits that objects with features that are human-like, that look and move almost—but not quite—like actual human beings, elicit visceral feelings of revulsion in many people. The “valley” in question refers to the change in our comfort with these objects: Our comfort level increases as the objects look more human, until, suddenly, they look simultaneously too human and not quite human enough, and our comfort level drops off sharply, only to rise again on the other side of the valley when something appears and moves exactly like a human being. It is in this valley, the realm of the too human but still not human enough, that dolls have taken up residence, and it is this valley that seventeen writers invite you to visit.

Excerpted from The Doll Collection © Ellen Datlow, 2015